In London Was Ours: Diaries and Memoirs of the London Blitz, author Amy Helen Bell writes:

Diarists’ and memoirists’ descriptions of London during the Blitz were heavily indebted to modernist metaphors. Civilian writers used metaphors of reading, watching films and photography to link raids to the familiar, and to emphasize their own importance as viewers. Like the Crimean soldier and the Great War journalist in London, Londoners during the Blitz were awed, saddened and excited by what they saw during the Blitz, and by their own privileged position as witnesses. The use of modernist and surrealist imagery points to the new artistic and historical interrelationship between the spectator and the London they watched.

This is a fascinating book and I’ll be posting more excerpts as I read.

From the book’s paperback cover: A milkman delivering milk in a London street devastated during a German bombing raid. Photo by Fred Morley.

Bill Brandt, 1940. Taking shelter in the Elephant and Castle tube station.

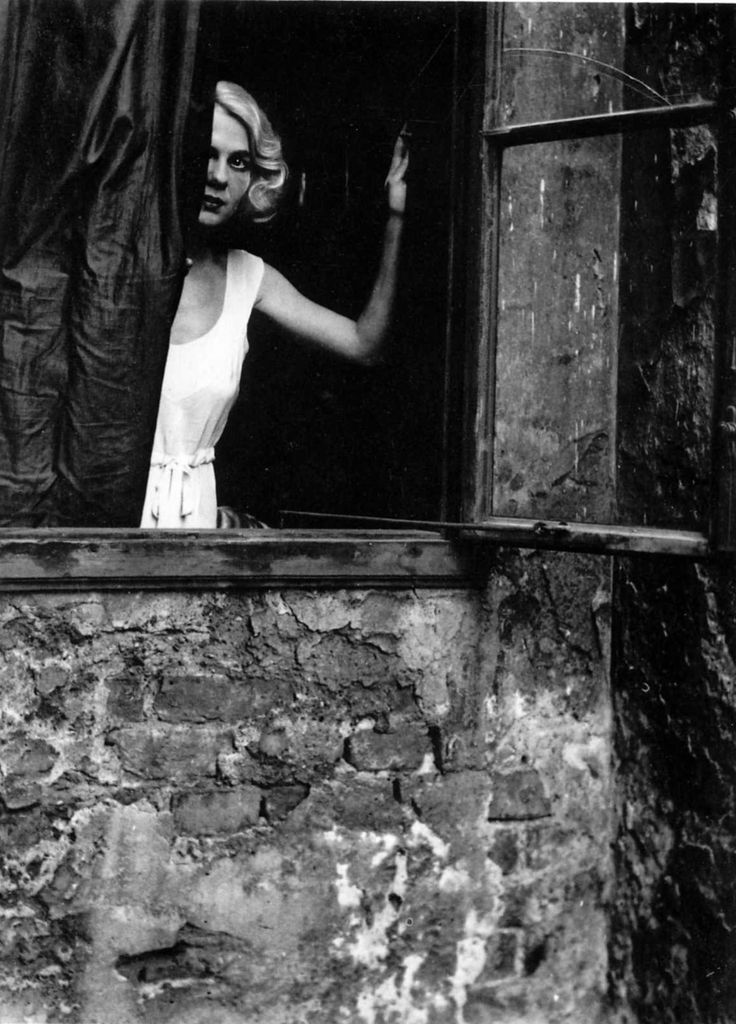

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920)

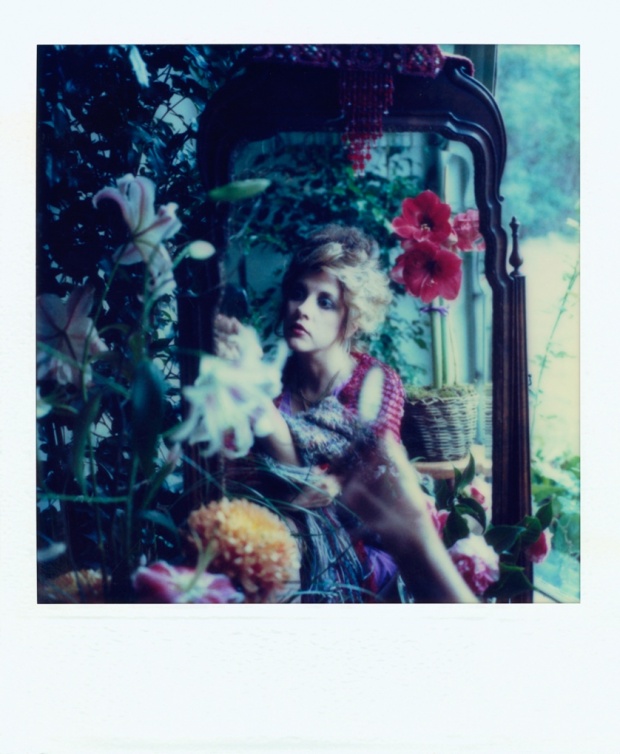

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) Metropolis (1927)

Metropolis (1927)