There’s a kind of poetry in these found objects, shot by Elena Dijour in Paris.

posted under: europe

two cupids in a paris flea market

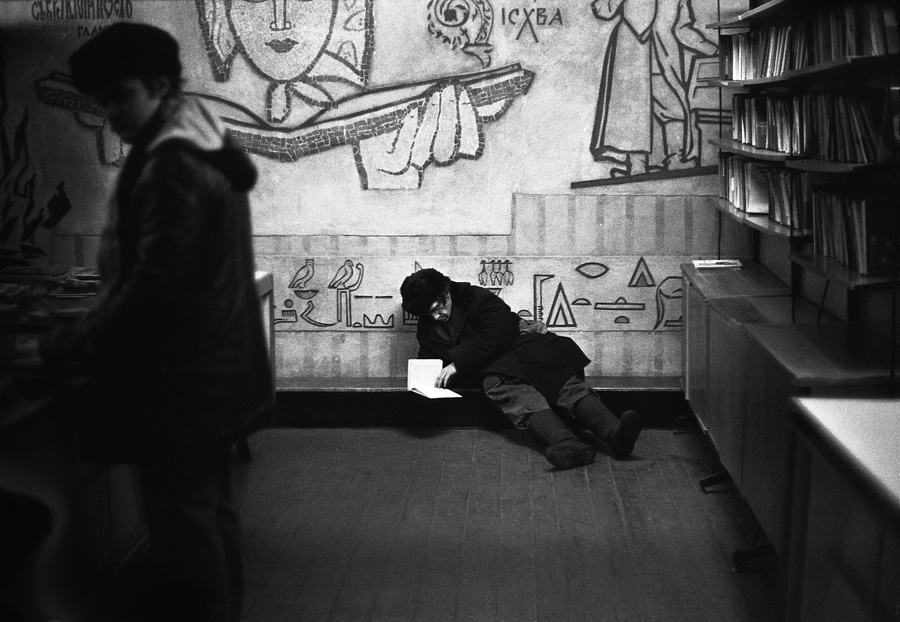

more vladimir sokolaev

new site photos: the latvian national ballet

New photos on the site are of dancers from the Latvian National Ballet, shot by Anna Jurkovska. Anna lives in Riga and is working on a longterm project documenting the company backstage, in rehearsal and in performance. The project, which she hopes to publish as a book, is called Sotto Voce. Anna has posted a lot of her project photos here. She has also photographed the Latvian National Ballet’s performance of Swan Lake, which you can view here. You should take a look at her photos of India, too.

christmas truce letter from the trenches

From the Guardian:

From the Guardian:

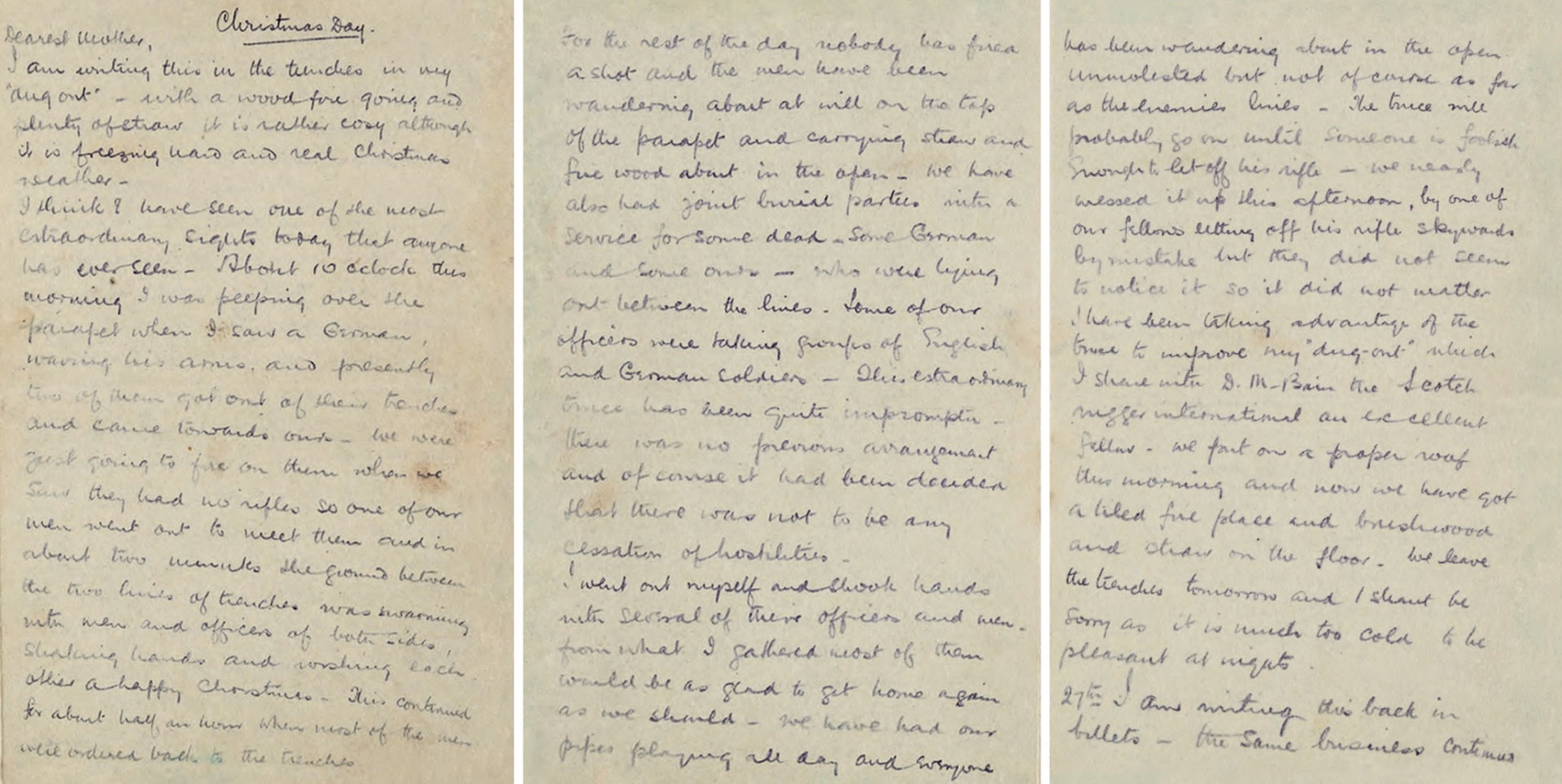

It was penned 100 years ago in the freezing trenches of the western front; a letter from a British army officer to his mother describing in vivid detail the extraordinary Christmas truce as soldiers from both sides laid down their weapons.

Second Lt Alfred Dougan Chater, of the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, writes of the moment when the men met in no-man’s land, exchanging souvenirs and cigars as impromptu truces were held along parts of the front between Christmas and New Year, with joint burial parties for the dead.

The letter has been reproduced by the Royal Mail, with permission from the Chater family, to mark the anniversary of the historic truce and the role played by the postal service during the first world war.

Remarkably, Dougan mentions nothing about Sainsbury’s or having a Sainsbury’s branded experience of the truce that day in 1914.

Dated Christmas Day and signed “Dougan”, the letter reads: “Dearest Mother, I am writing this in the trenches in my ‘dug out’ – with a wood fire going and plenty of straw it is rather cosy, although it is freezing hard and real Christmas weather.

“I think I have seen today one of the most extraordinary sights that anyone has ever seen. About 10 o’clock this morning I was peeping over the parapet when I saw a German, waving his arms, and presently two of them got out of their trench and came towards ours.

“We were just going to fire on them when we saw they had no rifles, so one of our men went to meet them and in about two minutes the ground between the two lines of trenches was swarming with men and officers of both sides, shaking hands and wishing each other a happy Christmas.

“This continued for about half an hour when most of the men were ordered back to the trenches. For the rest of the day nobody has fired a shot and the men have been wandering about at will on the top of the parapet and carrying straw and firewood about in the open – we have also had joint burial parties with a service for some dead, some German and some ours, who were lying out between the lines.”

He writes of shaking hands himself with several of the German officers and subsequently describes another “parley with the Germans in the middle” where cigarettes and autographs were exchanged and “some more people took photos”.

Watch the Sainsbury’s 2014 Christmas commercial ‘Christmas is for sharing’ and read my post about it here, or listen to what Russell Brand thinks of it here.

For some real, unbranded history, visit the First World War galleries on the Imperial War Museum’s website.

russell brand on sainsbury’s christmas ad

Yes, in their 2014 Christmas commercial that re-imagines the 1914 Christmas truce, Sainsbury’s has reduced World War I to nothing more than a branding opportunity to exploit. Which means they’re also exploiting the people who died after this historical event ended and killing resumed. It’s a piece of history they’re trying to rebrand as a Sainsbury’s feel-good moment, and it’s a cheap manipulation, an attempt to transfer some of the mythology of that poignant historical moment to the Sainsbury’s brand. As Russell says, ‘football, love, chocolate — is nothing sacred?’ You can read my original post on Sainsbury’s 2014 Christmas commercial here.

sainsbury’s christmas truce, 1914

In the last of the series for 1914, veterans of the First World War recall the few hours of impromptu ceasefire on 25th December 1914, when German and British troops mingled and played football in No Man’s Land on the Western Front. Drawing on the recollections of soldiers in the oral history collection of the Imperial War Museum and the BBC archive. Narrated by Dan Snow.

There are now no living veterans of WW1, but it is still possible to go back to the First World War through the memories of those who actually took part. In a unique partnership between the Imperial War Museums and the BBC, two sound archive collections featuring survivors of the war are brought together for the first time. The Imperial War Museums’ holdings include a major oral history resource of remarkable recordings made in the 1980s and early 1990s with the remaining survivors of the conflict. The interviews were done not for immediate use or broadcast, but because it was felt that this diminishing resource that could never be replenished, would be of unique value in the future. Among the BBC’s extensive collection of archive featuring first hand recollections of the conflict a century ago, are the interviews recorded for the 1964 TV series ‘The Great War’, which vividly bring to life the human experience of those fighting and living through the war.

larry fink: paris, 1998

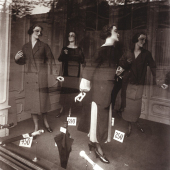

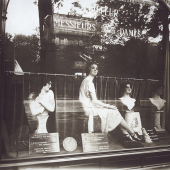

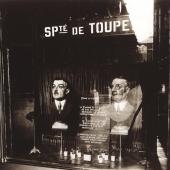

eugene atget

Six photos of Paris by Atget, from two books: Paris – Eugene Atget published by Taschen and Atget by John Szarkowski, published by MoMA. The latter book includes 100 plates with text by Szarkowski, much of which I found overwritten to the point of being intrusive. A typical example is his last paragraph accompanying the first photograph in the gallery below; it adds a layer of speculation that is not only indulgent, it distracts from the experience of viewing the photo.

Across the street from the Gobelins factory is a department store. Department stores changed the traditional ways of commerce and social interchange, and were therefore perhaps as unsettling and offensive to Atget–on the level of cultural and political principle–as shopping malls have been in our time to photographers such as Robert Adams. Nevertheless, it is wrong and self-defeating to photograph badly the subjects of which one disapproves. In fact, for a photographer as serious as Atget, it might be necessary to photograph a subject as well as he can before he knows what he thinks of it.

While Szarkowski does provide valuable context to many of the photographs, he too often, in passages like the above, tries to dazzle us with his references and asides, but ends up competing with Atget on the page. I much preferred the essay ‘Archive of Visions – Inventory of Things’ by Andreas Krase in the Taschen book.

Lacroix show, Paris, 1998.

Lacroix show, Paris, 1998. Vivienne Westwood, Tatiana Sorokko, Paris, 1998.

Vivienne Westwood, Tatiana Sorokko, Paris, 1998.